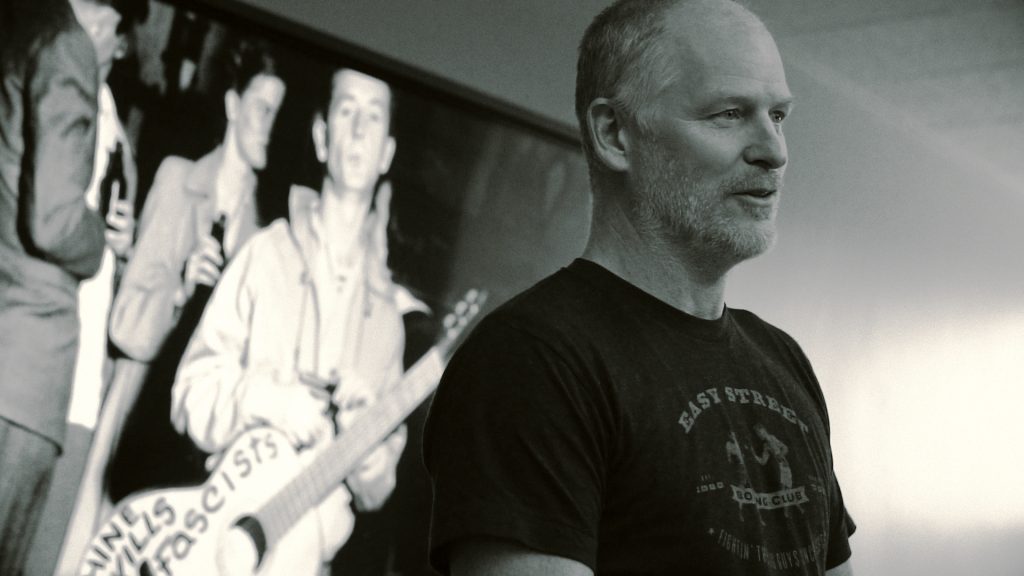

Easy Street Records’ Matt Vaughan Finally Takes Center Stage (Before a Lucky Few)

If music history is one of your interests, a schooling from Easy Street Records owner Matt Vaughan might rank up there with seeing Jimi Hendrix at Sick’s Stadium, Heart at Seattle Center Coliseum, or Pearl Jam at the Off Ramp. Odds are, though, like the chances of having “been there” for those concerts, you didn’t see Vaughan’s “How I Made It to Easy Street” talk at Seattle Public Library’s Southwest branch on Sunday—because only fifty people could attend.

Vaughan has lived and breathed Northwest music lore since childhood. His mother basically formed, and then managed, Queensryche. He worked in his first record store while a young teen. He managed the band Gruntruck. He’s hosted scores of celebrated artists and acts in his record stores, and befriended many of them. And he reveres the place Seattle holds in American music history.

Vaughan shared his experience, wisdom, and reverence in a small upstairs room that replicated the atmosphere of the mythical “secret” show. People not on the short RSVP list were turned away due to fire code restrictions. (The unenviable “bouncer” was event organizer Jeff McCord, Executive Director of the Southwest Seattle Historical Society. Vaughan’s talk was part of their “SouthWest Stories” series.) Background music (Woody Guthrie) played while the small crowd seated itself and anticipation thickened the air. Younger people in Pearl Jam and Soundgarden shirts and hats exchanged knowing glances. Older ones in who-cares dress exuded old-school West Seattle cool. And as Vaughan silently readied his Macbook, turntable, and rows and stacks of special records, the room was rapt with attention. Over an hour later, when extended an invitation to take a bathroom break, no one accepted. Every anecdote and aside was can’t-miss listening.

And in the two hours Vaughan was allotted, there were many. A sampling:

- The amazing historical, musical significance of the 18th and Madison corridor—where Ray Charles, Quincy Jones, Jimi Hendrix, and Macklemore all blossomed, and where Guthrie and Pete Seeger’s Commonwealth Federation Club held “folky leftist hootenannies.” Also, just blocks away, clubs like Savoy, Birdland, and Washington Social Club birthed music, and open-minded black and white performers, that would “change the world.”

- West Seattle’s unique role in the creation of multiple career-shaping songs, albums, and bands—from Ray Charles’ early work on Harbor Island to the Ventures making Walk Don’t Run on Admiral Way to Mudhoney and Pearl Jam members calling the neighborhood home to Sir Mix-a-Lot playing Easy Street’s first in-store.

- Vaughan’s role in naming local band Striker at ten years old, after soccer practice, while in a car with his mother and Clive Davis.

His father’s Navy career taking him to the Pentagon and the Oval Office as an aide to President Bill Clinton. - His grandmother’s founding of the surf-apparel company Hang Ten.

- The rise and fall of Easy Street’s Queen Anne location.

- How Pearl Jam, a group of guys he “would walk through hell carrying buckets of gasoline” for, came to perform at Easy Street for a lucky crowd of about 150.

- The Beastie Boys’ night digging through Easy Street crates to establish a record collection for Mix Master Mike to use during their tour.

- The tenacity and perseverance of Macklemore, who sold CDs on consignment long before anyone knew who he was.

- How a bookkeeper embezzled $200K from Easy Street and has been on the lam ever since.

And, of course, Vaughan related how he became owner of an independent record store as a teenager (however legally tenuous at first), and stuck with it through myriad struggles to essentially invent things like the in-store artist performance and, through a small coalition of indie shop owners, the modern vinyl-worshipping juggernaut that is Record Store Day.

The loose through-line of Vaughan’s talk: that Seattle’s music scene may have repeatedly morphed and reinvented itself since the days of Guthrie, but it’s always been comprised of liberal-minded people with progressive ideas perhaps “too dangerous” for other places. It’s been a community that’s worked together rather than fought itself. It’s been a family of sorts, sometimes competitive but ever supportive of its individual members’ goals.

Vaughan complemented this message with a photo slideshow that touched on all he covered—and much more. There was the expected (Kurt Cobain; Eddie Vedder; artists performing on Easy Street stages) and surprising (Guthrie; young Charles; himself, bloodied on a gurney, at Sasquatch). He also provided audio context for the topics he related, playing snippets of songs (both well-known and obscure) through his phone and turntable.

Of course music is of supreme importance to Vaughan; he’s built a lasting career on it. But you could see its profound pull on the man with each sample he played. Once there was a beat or vocal, he hesitated to lift the needle or tap pause. He moved his head in time—to Charles, Sir Mix-a-Lot, Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Macklemore—and let each song linger as long as he could.

If Vaughan’s talk lacked anything, it was stage comfort. He’s clearly comfortable with himself—you could see that in his Easy Street t-shirt, low sling of his belted jeans, and easy way he moved—but being front-and-center seemed to rouse a little anxiety. He spent long moments now and then considering his next topic. He forgot his slide show more than once, then zipped through scores of photos in his final minutes. But who would hold a little distraction and uneasiness against him? As Vaughan joked, he wasn’t accustomed to being the headliner.

But perhaps this event will change that. In the days since, he and McCord have discussed the possibility of another event—“a follow-up talk at a larger venue,” according to McCord, “and a benefit for the Southwest Seattle Historical Society.” McCord noted via email that they will continue discussions early next year. They’re aiming higher than a 50-person audience, and rightly so.

You could call this potential second appearance an encore, but by all indications, Matt Vaughan’s performance is nowhere near complete. He still has a record store to run, and could easily parlay his history, wisdom, and enthusiasm into a memoir or script or syllabus. (As he said himself at the library, “If you think you’re done in your 40s or 50s, you’re wrong.”) You have to believe that as long as there’s music, Vaughan will want to share it, one way or another.

That’s how you make it to Easy Street: by embracing the thing that you love.

Photo credit: Ryan Cory (IG: @ryan.cory) Cory also filmed this event, and the video should be available on the Easy Street site by late November.

To learn more about West Seattle’s role in our city’s rich music history, visit Southwest Seattle Historical Society’s Log House Museum on Alki. Its “Sound Spots” exhibit, on display into early 2019, highlights the neighborhood’s contributions. Admission is free.