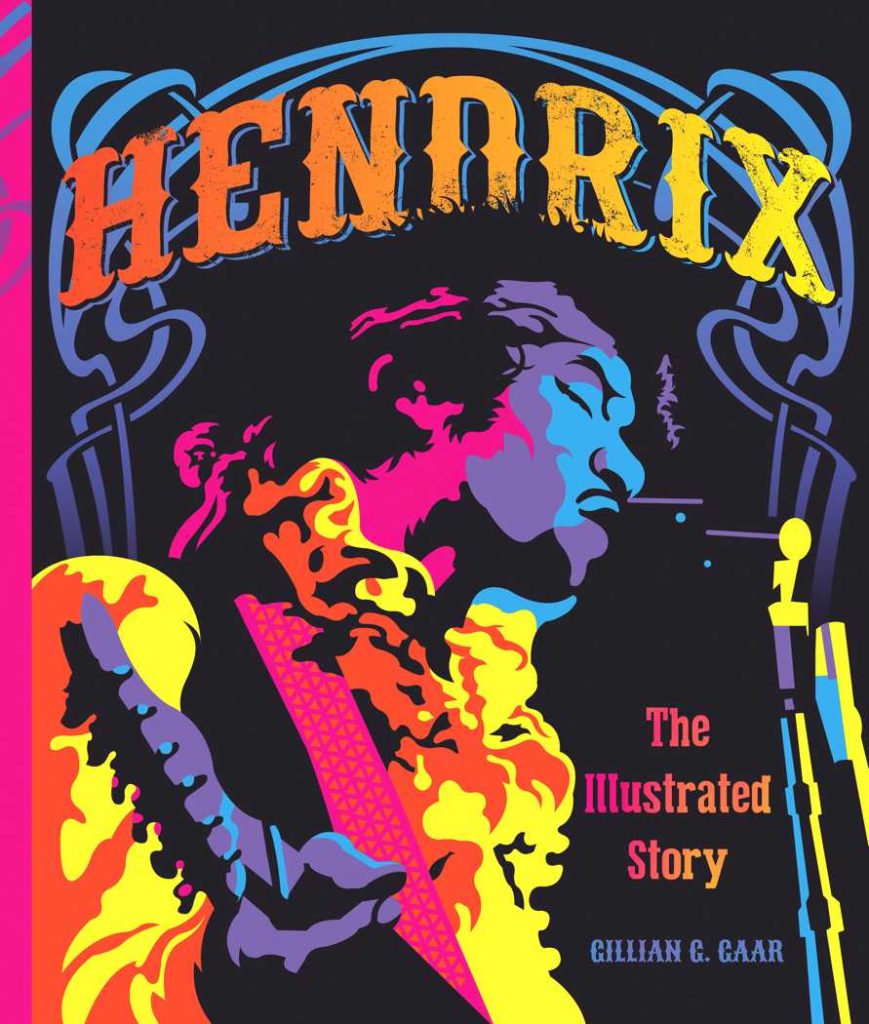

Read this excerpt of upcoming Hendrix book; ‘Hendrix: The Illustrated History’

In this excerpt of “Hendrix: The Illustrated History” (Voyageur Press), Gillian G. Gaar looks at how Jimi Hendrix’s legacy has changed in his hometown of Seattle over the years. The book will be released on October 1, 2017, more info can be found HERE.

In the 1980s, the advent of CDs revived interest in Jimi’s back catalog, which was reissued. Sales were booming; in 1988, Forbes magazine estimated income from Jimi’s records and publishing to be $4 million a year, with merchandising adding another $1 million.

Despite this, Jimi found it hard to get recognition in his hometown. In 1980, Seattle radio station KZOK sponsored a fundraising drive to erect a memorial to Jimi. But the city authorities were resistant, pointing to Jimi’s drug use, which, in their eyes, made him a poor role model. “It was hell dealing with the city,” Janet Wainwright, then the station’s promotion director, told the Seattle Times in 2011. “We tried everything. Naming a street, one of those little pocket parks you see at the end of some streets. Nobody was interested. I was met with the most vehement objections, including from Walter Hundley, head of the Parks Department, who sat me in his office and basically said they were not going to memorialize a drug addict.” Wainwright also recalled getting hate mail, “death threats, people saying Jimi Hendrix was Satan.”

Finally, David Hancocks, then director of the Woodland Park Zoo, offered the zoo grounds as a location for a memorial. A mosaic walkway was designed in the zoo’s African Savannah section, leading to a “Jimi Hendrix Overlook,” which overlooks a rock with a commemorative plaque. The memorial was unveiled in 1983, with Jimi’s father Al Hendrix in attendance. Some thought it was racially insensitive to have the plaque in the African Savannah part of the zoo, but Al didn’t mind, simply telling reporters “Jimi liked animals.” But the memorial wasn’t well maintained. The rock was at one time heated — making it a “hot rock,” in reference to Jimi’s music — but the heating element eventually stopped working. Not that anyone observing the rock would know; visitors weren’t allowed to touch it.

In 1984, a bust of Jimi by local sculptor Jeff Day was donated to Garfield High School, where it’s still on display in the library. Day recalled the school was initially hesitant to take the bust, again due to Jimi’s use of drugs. And he was surprised to be questioned about the issue during the dedication, telling reporters in response that he felt it would be inspirational, because of how Jimi overcame his impoverished upbringing. Fred Dente, who had helped to raise funds to cover Day’s expenses, wrote a bitter account of the event in a letter to The Rocket, Seattle’s music paper, complaining that the school’s principal refused to let students take part in the ceremony. “KING TV was there, and reported that some in the administration felt that Jimi was a bad role model for the students, along with usual references to Jimi’s substance use and abuse. I’ll never forget that day, and the embarrassment I felt for the Hendrix family.”

November 27, 1992 would have been Jimi’s 50th birthday. In a sign that times were changing, Seattle mayor Norm Rice issued a proclamation citing the date as “Jimi Hendrix Day,” the first official recognition Jimi received from Seattle’s city authorities. Sammy Drain, a friend of Jimi’s, had approached the mayor about issuing the proclamation, and he readily agreed; as a mayoral aide stated, “The mayor felt that someone who had contributed to the music industry as Jimi Hendrix had, there was no question he deserved honor and recognition in his hometown.”

###

In the 1990s, Jimi’s family began ramping up their fight for control of Jimi’s music and image. “I don’t know what was tougher — going through World War II or battling for Jimi’s legacy,” Al later wrote in his memoir, about the legal battle that commenced in 1992.

In the fall of that year, Al’s lawyer Leo Branton sent letters to Jimi’s brother Leon Hendrix and Janie Hendrix (adopted by Al as his daughter when he married Janie’s mother, Ayako Jinka), on behalf of Al, asking for them to waive their contingent reversionary rights to Jimi’s music, in exchange for a cash payment. Leon signed; “My drug addiction was more important to me than anything else, and scrutinizing business deals was of little interest,” he said in his memoir. But Janie, believing Jimi’s legacy was worth more, did not, and hired legal representation. To her surprise, she learned that Branton had been negotiating a deal with MCA to buy the rights to Jimi’s music, which were then owned by the various off shore companies Branton had set up. “Jimi had control of his masters,” Janie explained to Celebrity Access. “So all of the masters ended up being signed over as a sale to these off shore companies. However, my dad was told it was a licensing agreement … In 1993, we discovered that these offshore companies had ownership.”

On April 16, 1993, Al sued Branton, for “breach of fiduciary duty, fraud, negligent misrepresentation, legal malpractice, restitution based upon rescission of contract, securities law violations, infringement of copyrights, infringement of rights of publicity and declaratory judgments.” Branton responded by filing a countersuit, for defamation of character.

The legal wrangling went on for two years. Seattle billionaire Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft and a huge Hendrix fan, loaned the family $5.8 million for legal expenses. Allen was making plans to open a Hendrix themed museum in Seattle, which would feature many of the collectibles in his own collection. But there was a falling out — temporary, as it turned out — between Allen and the Hendrix family, when Allen also wanted rights to Jimi’s likeness and music. “They wanted too much, too hard, too fast,” said Janie.

The lawsuits were ultimately settled in 1995, with Al winning back the rights to Jimi’s music and image. It wasn’t without cost; it was agreed that $9 million would be paid to the defendants. The family soon set up Experience Hendrix, the company that would oversee Jimi’s legacy from that point on, with Al made Chairman of the Board, Janie becoming President, and Bob Hendrix, Jimi’s cousin, Senior Vice President. A licensing deal with MCA was struck, and Experience Hendrix set up its own labels as well; Hendrix Records (jointly run with MCA), which released material by new artists, and Dagger Records, which released Jimi’s live shows via mail order.

By a happy circumstance, a Jimi Hendrix tribute concert was planned for that year’s Bumbershoot festival, Seattle’s yearly arts festival held over Labor Day weekend at the Seattle Center. As early as 1992, Norm Langill, the president and founder of One Reel, the company then producing Bumbershoot, had thought of having the festival host a Jimi Hendrix Electric Guitar Competition. Langill took the idea to the Hendrix family, who were interested, but were more concerned with their ongoing litigation at the time.

But 1995 was not only the 25th anniversary of Jimi’s death, but Bumbershoot’s 25th anniversary as well. The Hendrix family had wanted to stage a commemorative festival, but met resistance from city officials. Then Langill stepped up. “I listened to Jimi a lot in the ’60s,” Langill told the author in 1997. “I remembered being in Seattle when he died, and they wanted to do a concert for him then. Which would have been very natural at the time, but it never happened. So I said, ‘Why don’t we do the concert for Jimi now, at the 25th anniversary?’”

The Hendrix family agreed. The guitar competition was also a part of the event, and there was also a Hendrix “Red House” exhibit, displaying memorabilia and personal artifacts, such as the drawings Jimi had done as a child.

But the main event was the Jimi Hendrix Tribute Concert, held on September 4 at the Seattle Center’s open air Memorial Stadium. There were opening sets by Abraxas and George Clinton and the P-Funk All Stars, followed by an all-star guitar finale. Noel Redding, Mitch Mitchell, and Buddy Miles were among the musicians — the last time all the men would share the same stage. Other performers included Eric Burdon, Heart’s Ann Wilson, Living Color’s Vernon Reid, and Pearl Jam’s Mike McCready, among others. Hendrix tribute artist Randy Hansen was featured; so was Jay Roberts, the 29-year-old winner of the guitar competition.

Al Hendrix was honored, coming out on stage to a loud ovation. To his surprise, he was given a gold crown and red robe to wear, and, after lighting a specially designed torch that featured a guitar on top, was led to a throne at the side of the stage (he later jokingly noted that the sound wasn’t very good from that position). Four paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division also dropped into the Stadium, in acknowledgement of Jimi’s own days as a Screaming Eagle.

The show ran late, and was further hampered by a thunderstorm. “I remember at one point Buddy went on a tear for about 45 minutes — almost 25 minutes more than he was scheduled to play,” Langill said. “And this big thundercloud passed, and Narada [Walden, the show’s musical director] turned to me and said, ‘That’s Jimi telling Buddy to get off the stage!’ And it did sort of feel like Jimi was up in the thunderstorm, that there was this hovering electric magnetic presence. That sounds a little goofy, but you couldn’t help but feel that way. ‘Cause it’s so odd to have a lightning thunder storm in Seattle.” There was another eerie moment at the show’s beginning, when a flock of 100 Canadian geese flew in a V formation straight up the stadium, and over the top of the stage. “Everybody looked at them and thought, ‘Wow, that was weird!’” Langill recalled. “There were a lot of natural forces in play that night. But heck, you remember that until the day you die, that it had those kind of forces of nature.”

The next morning, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ran a photo of a teary-eyed Al on the front page. “This festival was yes, to honor Jimi,” Janie told Goldmine, “but more so to show my dad the love that the fans have for Jimi, and to let him see how big Jimi was. ’Cause I don’t even think up until that point he really realized that Jimi was as big of an artist, still, as he was. So he was really touched. And I remember after the concert someone came up to him and said, ‘Well, Mr. Hendrix, was it everything that you wanted it to be?’ And he said, ‘No. It was more.’ And that really touched my heart ’cause we did it for him.”

###

And if the city of Seattle was still largely resistant to having a public memorial for Seattle’s most famous musician, private individuals were increasingly stepping up to make their own contribution. In 1993, a beautiful mural of Jimi was painted on the wall above Myers Music at 1204 1st Ave., the shop where Al had bought Jimi his first electric guitar. The mural was painted by Dan and Mae Hitchcock, who had previously painted murals and sets for clients ranging from Phil Collins to Southwest Airlines. The mural was unveiled on November 27, Jimi’s 51st birthday. As luck would have it, there was an APEC conference in town at the time, meaning there were numerous journalists on hand. “It was a Sunday, and the journalists didn’t have anything to do,” Dan Hitchcock later recalled. “The story went all the way to China; we got clippings from everywhere from that mural.” A commemorative plaque was also installed. Sadly, when the building was sold, the mural was painted over.

In 1997, another memorial appeared on the corner of Broadway and E. Pine St. in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, outside what was then the headquarters of AEI Music (a company that produces background music tapes for various businesses). The company’s president, Mike Malone, oversaw what he called the company’s “alternative corporate art collection,” which included guitars owned by Bill Haley, Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, John Lennon, and Jimi Hendrix (a 1970 Fender Stratocaster Sunburst). He also commissioned statues of each artist, made by Seattle sculptor Daryl Smith at Seattle’s Fremont Foundry. Smith chose to have Jimi on his knees, leaning back as he plays, wearing an outfit patterned after the clothes he wore during the Monterey Pop Festival.

The other statues were placed around AEI’s offices. But Malone wanted to have Jimi’s statue outside, working with the neighborhood’s Chamber of Commerce and other community organizations, with AEI paying for the complete installation. The statue was unveiled on January 21, 1997, with Al and Janie in attendance. It was the first time they’d seen the statue, and Smith was nervous. “If they had been disappointed or hadn’t liked it, I would’ve been crushed,” he told the author in 1997. “But they liked it real well. Al got tears in his eyes when he saw it; he kind of got misty, so I could tell it had an effect on him.”

Despite the rain, over 100 people turned out for the event. Malone held up Jimi’s guitar for the crowd to see, and Randy Hansen played a short set, through clouds of purple smoke. The statue remains a popular photo op destination, due to the high foot traffic in the area. Smith was happy the Hendrix statue was chosen to be outside: “I’m glad it turned out to be Jimi Hendrix. It’s really appropriate. Having grown up down by Leschi Park, I’m sure he spent a lot of time on Broadway. And I suppose that often he walked right over that sidewalk. I think that’s cool, that he’s back on Broadway!”

“Hendrix: The Illustrated History” (Voyageur Press), will be released on October 1, 2017, more info can be found HERE.